Between 1965 and 2007, Ed Ruscha visualized queer sites on Sunset Boulevard. In so doing, he captured a social world that had to remain unseen while being seen—before and after Stonewall and Gay Liberation.

Particularly when combined with other sources, his seemingly indiscriminate and repeated documentation of Sunset (among other major streets of Los Angeles) yields a visual history showing how queer places, along with their social and cultural history, changed over time.

Just as queer life and culture required other kinds of knowledge to make sense of the world and navigate it, so do Ruscha’s photos. The limit of his approach towards social and cultural history, in general, is that it cannot be fully understood simply by observing façades and streets with some (unwanted) cars on them. One needs to gather additional supporting evidence—such as other photographs and oral histories—from additional resources, and then connect those to Ruscha’s work. This is particularly so when using his photographs to explore the history of queer life in twentieth-century Los Angeles.

Since queer life and culture in the United States had been sanctioned, forcing queerness to stay off the grid, queer subjects developed ambiguous, semi-visible aesthetics as well as cultural and social practices. Generally, these practices and the places and spaces queer subjects created were only obviously queer for those who knew, who could decode the signs. In addition, for protective reasons they were documented only rarely, which, in turn, makes queer historiography challenging in terms of both material evidence and scholarly ethics. Since supporting materials cannot easily be found in city or state archives, and sometimes not even in queer archives, they need to be gathered from multiple, even unusual sources. All the while, one hesitates to make queer life public, while simultaneously acknowledging that we can only write queer histories by working against such caution. As much as Ruscha’s work reveals a history of queer culture, however, it equally protects that history; his consistent camera’s eye neither exploits nor overtly exhibits queer LA. Looking closely, Ruscha’s photographs signify and suggest glorious stories behind the façades.

To this end, this essay begins with select cases among more than 50 known queer sites on Sunset, identified through historical travel guides, and then explores them further through Ruscha’s photographs. Most significant among these travel guides was Bob Damron's Address Book, published by Damron from 1964 on (shortly before Ruscha’s first Sunset photography campaign), which helped queer subjects identify queer or queer-friendly places, such as bars, bathhouses, restaurants, clubs, cruising spots in parks, hotels, and bookstores throughout the United States.1 Damron, an LA native, became a pioneer in queer guides due to his own experience of the vast city of Los Angeles, with its LGBTQ places spread out across town.2

As much as Ruscha’s work reveals a history of queer culture, it equally protects that history; his consistent camera’s eye neither exploits nor overtly exhibits queer LA. Looking closely, Ruscha’s photographs signify and suggest glorious stories behind the façades.

Research projects based on these guides, such as Mapping the Gay Guides or Queer Maps, inevitably reproduce the guides’ limitations, such as their partially anecdotal or false entries, most of which were written by and for those privileged to travel: white gay men.3 But compared to the early Damron guides’ unillustrated listing format, these later mapping projects make it visually alluring to travel through a city’s queer topography, and they help reveal queer nodes. That’s true even in vast cities like LA, where cartographic elaborations of gay/queer guides show two key areas along Sunset where one would find the sites taken up in this essay: West Hollywood and Silver Lake.

The stories of contemporary witnesses further illuminate those sites and Ruscha’s photographs. Oral histories and other narrative accounts necessarily help correct the guides’ shortcomings, as anecdotal as they may be. So, while our knowledge of historical queer topography is based on fragments and queer gossip, these should not be disregarded but appreciated as discourse that helped queer subjects navigate through largely hostile surroundings.4 Such stories, unfolding during the very years of Ruscha’s own transits, indicate what his photographs explicitly reveal and what they hide, obscure, or merely suggest. The social history behind the photographs helps us see Ruscha’s images anew. Or, put differently, imaging needs imagining.

Every Building? Tracing Lesbian In_Visibility

At the most basic level, Ruscha’s photographs help us recall the forgotten by revealing both traces and the presence of absence. For example, lesbian bars on the Sunset Strip had a heyday in the 1930s and ‘40s, but today their past presence is largely invisible. Ruscha’s photographs recover the physical legacy of at least two such venues: Cafe Internationale and Jane Jones’ Little Club. The central question here is not how these queer sites changed over time—because they had already been closed for decades before Ruscha started his project in the 1960s. At issue, instead, is the search for visual evidence of these sites and what that evidence tells us about their lasting reverberations.

Cafe Internationale (also known as Tess’s or Tess’s Continental) was a lesbian bar with male impersonator shows located at 8711 Sunset Boulevard from the late 1930s until 1942.5 Before the building became a lesbian bar, it was home to Mammy Louise’s Bayou and, according to one author and blogger, “run by a black woman named Louise Brooks.” Their account continues: “Something dodgy was going on because Mammy Louise’s Bayou was raided in the fall of 1938 and subsequently went under.”6 Although both businesses were gone by the time of Ruscha’s survey, his photographs demonstrate, perhaps surprisingly, that the original building that housed them still remained.

Ruscha’s photographs also show a history of constant change on the site from 1966 to 2007 (and beyond), albeit one that never fully wiped out clues of the building’s past as the Black-owned Mammy Louise’s Bayou and the lesbian-serving Cafe Internationale. By 1966, significant alterations had taken place at this site. Now home to the restaurant Cyrano, named after the intersecting street, the building appears to have been painted, the little lawn and some bushes in front of it had been removed, and, most symbolically, the architrave that once read “Mammy Louise’s Bayou” now announced “CYRANO.” What’s more, a new, low-rise addition appeared to the original structure’s west. By 1985, there was no sign of a restaurant here anymore. The balustrade facing the street had been torn down and turned into a parapet, the whole ensemble painted in a light color, and the porch enclosed with windows. But through it all, the original building remained visible, even despite the major alterations recorded during Ruscha’s 2007 visit. By then, a massive new wall—with a large shop window and door into a fashion store—obscured the façade of the original building. A decade later, a new tenant had enclosed the antique-like temple or sunroom front of Mammy Louise’s Bayou behind glass.7 Today, according to Google Street View, the building houses a dental office with the former wintergarden’s columns still intact. Despite all these alterations in architecture and use, traces of the past can still be found and followed through the photographs. These especially include those columns and a tin roof, the last bits of a queer history that subsequent uses could not fully obliterate.

The lesbian nightclub Jane Jones’ Little Club began operating at 8730 Sunset Boulevard in 1936. Its fate contrasts with that of 8711 Sunset. Once a glamorous lesbian club run by the actress Jane Jones, it quickly became a target of police raids for serving liquor after legal hours—a common pretext for shutting down queer bars, which ultimately worked in this case. By 1939, the club was closed. What remained cannot be seen in Ruscha’s photographs because the charming Spanish-style building with a hotel-like awning (also used for an illustration of the club on a book of matches) did not exist anymore in 1966. The building was replaced by a big corporate building in 1961 which then housed the Continental Bank and later became known as the Law Building.8

Over the decades (and including until now) large parts remained for lease, a tale told by the façade’s signs. There are no lasting architectural elements to point to here, nor even a trace of the building. But in the ultimate erasure of Jane Jones’ Little Club, once known, is—perhaps—evidence of the repression, antagonism, and precarity that such sites regularly confronted, in the face of both officials who did not want them there and the forces of real estate that were indifferent to such histories. The invisibility of this club's queer past in Ruscha's photos is symptomatic of vanished queer sites more broadly. Ruscha could only (indirectly, accidentally) document this shift from a little club to a potentially more profitable office building. Ruscha’s photographs, here, reveal the presence of absence that's a common feature in queer culture.

Ruscha’s photographs underline the importance of visually documenting buildings in a city where, in just a matter of years, a wintergarden could be stripped down to its columns and put behind glass or a one-floor club could become a modern tower. Even when no traces persist, historical imagery of a once-queer place changes the connotations of both fleeting remains in Ruscha’s photos and the sites themselves. Layered photographs and stories—by Ruscha and those who frequented the street before him—shift our perception of the city, revealing on the future sites of banks and dental offices the past efforts of both Black and lesbian women to make a place in Los Angeles. They also reveal that Ruscha's aim and claim to capture every building on Sunset was simultaneously true and false, a hyperbole and an understatement.

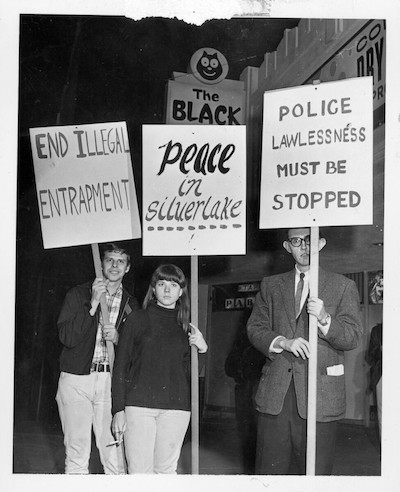

Against Homonormativity: The Black Cat

At the Black Cat bar at 3909 Sunset Boulevard, one of the first documented demonstrations against anti-queer police violence took place after a raid on New Year’s Day 1967, two years before the Stonewall Riots in New York City. This is the better-known part of its history. Today, the Black Cat at this same address is a queer-friendly restaurant and bar. Since the new Black Cat's opening in 2012, it has been operating at the supposedly first site of queer resistance in public. It is no coincidence that the website’s history section does not mention this latest incarnation’s year of opening. Instead, the website misrepresents the present establishment as directly related to the original Black Cat from the 1960s—even though other businesses operated at the site in the intervening years, and even as the current restaurant no longer caters to a predominantly queer clientele.9 A look at its historical iconography and social history, based on Ruscha’s images, offers a chance to understand the changes made beyond the façade. More than that, the photographs help describe what impact this address had (and has) on queer culture. Homonormative tendencies characterize the selection and glamorization of convenient queer histories today, but Ruscha’s photographs help interrupt that ideology of progress and continuity. His camera’s record offers access to queer narratives that are covered up by today’s Black Cat.

For example, the building housed the underground venue called Basgo's, the site of the weekly queer Club FUCK! event between 1989 and 1993. Historian Josh Kun describes this event as a party where “notorious live performances mixed blistering drum machine alt-disco with hardcore kink, nudity, and the occasional dildo-dangling go-go dancer.”10 Afterwards, it became the queer Latinx bar Le Barcito, itself evidence of the multiple queer-of-color communities who occupied space on Sunset.

Ruscha’s 2007 photograph shows us the presence of Le Barcito, registered in a sign visible shortly before the building was declared a historic site in 2008. It also shows how small the actual bar was before it became today’s Black Cat, which, at some point since 2012, expanded to encompass the former laundromat next door. Though difficult to see, Ruscha’s camera recorded Le Barcito’s pride flag rolled up around a pole or wire cable. And although the photographs were taken in broad daylight, the bar’s door oddly stands open.

At first, Ruscha’s visual evidence of queerness risks luring the viewer into the interpretative trap of melancholic nostalgia. The open door suggests that he might have documented the last days of Le Barcito, maybe even moving-out day. But because the bar was still operating until 2011, the pride flag and open door symbolize quite the opposite.11 They depict an example of what queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz has referred to as queer utopia, which he saw in, for example, Kevin McCarty’s photographs of empty queer club stages. Muñoz described such images—of latency, of absence—as evincing a “queer potentiality.”12

The affective potential of the Ruscha-depicted open door and unfolding pride flag is apposite to, and anticipatory of, journalist and DJ Liz Ohanesian’s description of the interior life of Le Barcito when in operation: “Decked out in glitter-flecked gowns and flashing beauty-pageant grins, the performers engage the crowd in a drag revue set completely to Spanish pop songs. If you’re itching to see drag queens lip-synch to songs that don’t involve Beyoncé, this is the place to go.”13 Ohanesian’s short description is an example of a potentially unreliable, obscure, but important resource for the study of queer imagery. Beyond a brief glimpse of the performers, it explains a queer space ex negativo ("songs that don't involve Beyoncé") and through colorful allusion, while excluding any description of the place itself, including its interior, the bar's owners or operators, guests, or DJs. Thus, this historical piece of information is itself queer: the queer Latinx people reading LA Weekly could relate and—if interested—visit, although not too much was revealed.

In an earlier era, more visibly instructive—albeit without being utopian—is the poster or adhesive foil with a black cat pin-up figure still present on the right side of the door in Ruscha’s 1973 photograph. No longer visible, however, was the cartoonish image of a black cat figure on the left side of the door that seems to have been removed after the raid in 1967. The remaining female pin-up, dressed in cat mask and tail, evokes, for example, Harold Hoffman’s horror film The Black Cat (1966), the Parisian Le ChatB Noir nightclub and cabaret, as well as Batman comics and live-action adaptations. These adaptations include the TV series under the same name (1966-68) with Julie Newmar and, later, Eartha Kitt as Catwoman, a sexual antiheroine with a cat mask and a tight black catsuit. Further conflations of the cat and sexuality can be found in the films Cat People (1942) and Lady of Burlesque (1943), both of which feature scenes with burlesque dancers in cat costumes. While the Black Cat’s exterior cat pin-up logo would not necessarily suggest a queer bar today, its allusion to sexual freedom was intelligible in the 1960s. Furthermore, the image might also have been an explicit reference to another early gay bar in San Francisco, the Black Cat Café. It too had used a sign with a black cat figure before it closed in 1963. In addition to these sexual connotations, a cat’s nine lives were also a symbol of resistance and survival. In multiple ways, the figure that Ruscha captured on film stood as a gay icon in the literal sense.

A third aspect of this site that Ruscha’s photographs partially reveal is the divergence between the Black Cat then and now. In particular, the comparison of the façade's contemporary aesthetic versus Ruscha's depictions retrospectively reveals and debunks the homonormative, chronological tale of progress and continuity the venue communicates today: as the story goes, a small queer underground place, shabby from the outside, glamorous on the inside, on its way to becoming a larger, more chic, and pricier restaurant and bar in a polished Art Deco building, catering to the general public. The photographs represent how unremarkable the original bar’s front was, and how much more square footage the laundromat next door occupied. Today, a visitor finds the rest of the story that unfolded after Ruscha’s final visit, without a trace of the structure’s red and white paint, or its days as Le Barcito, or its utilitarian longtime neighbor. The combined storefronts misleadingly suggest the historical Black Cat as one large unit, further homogenized with white paint and harmonized new windows.

Though themselves also a partial view, Ruscha’s images revise such homonormative narratives. They offer a picture without smoothed edges as, over decades, the now cleaned-up bar hosted queer underground events, offered its stage to liberatory performances across LA’s queer communities of color, persevered past police raids, and communicated its possibilities to those who knew how to read the signs. Today’s retro sign and plaque on the façade, and photographs of the 1967 demonstration on the walls inside, offer guests a streamlined and skewed view of only certain aspects of the bar’s queer history. Ruscha therefore provides a corrective to reductive strategies that make large parts of queer history invisible. This case also shows how quickly even Ruscha's relatively recent Sunset photographs have become historical artifacts due to the rapidly changing cityscape of LA. While they do not show today's Black Cat, they provide visual evidence that fact checks a bar adorned in borrowed plumes.

Circus of Books: Cruising the Shelves, Cruising Utopia?

Ruscha's photographs can only hint at a subcultural experiential knowledge, as evidenced by 4001 Sunset Boulevard, the longstanding bookstore called Circus of Books (1985-2016) that specialized in gay pornography and LGBTQ literature. Jewish married couple Karen and Barry Mason owned both Circus of Books locations, in West Hollywood and Silver Lake. The West Hollywood store, in particular, became a famous “gay cruising spot, place of refuge during the AIDS crisis, and mom-and-pop porn shop fighting federal obscenity charges.”15 After the Silver Lake location closed in 2016, so did the West Hollywood one in 2019.16

Circus of Books first appeared in Ruscha’s 1985 photographs, shortly after the shop’s opening. The storefront advertised its wares with the line “MAGAZINES AND BOOKS FOR ALL” along the bottom of its sign. This should not be disregarded as a pure eye catcher to attract customers; the subtitle was a political statement, too. Its subtext, clear to those to whom it was speaking, was that stigmatized gay men also deserved a place to meet; buy sex toys, videos, and porn magazines; and go cruising—in the middle of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

That a straight Jewish couple provided a platform for queer cruising at times of intense anti-queer hostility, stigma, and suffering—and that gay men kept having sex—can be seen as a form of queer utopia. Queer theory’s initial strand of antirelational and antisocial writings by, among others, Leo Bersani and Lee Edelman, criticized a supposed glorification of the pre-AIDS era as idyllic and full of wild sex.17 Subsequently, the aforementioned José Esteban Muñoz created an alternate framework for queer utopian perspectives on the past and present in a political effort to counter the negativity of queer theory in the late 2000s.18 Ruscha’s photographs can only hint at what Moira Kenney refers to as the “experiential knowledge … [that] forms a collective unconscious about the connection between the physical space of the city and the possibility of gay and lesbian empowerment.”19 Still, his images of Circus of Books provoke a feeling of hope and a memory of queer forms of knowledge, world-making, and being. Even if this potentiality cannot (and should not) be substituted by photographs, its appearance here hints at the possibility of this “queer utopian memory.”20 This is fully realized, for example, in the queer short film Strip Strip (c. 1968) by pioneering filmmaker Pat Rocco. In the film, a young man (Jerry Jones) purports to be walking down Sunset Strip while stripping off his clothes until he's fully naked, both overlaid with and against the backdrop of filmed footage of Sunset, with its flickering signs and streetlights.21

Ruscha's photographs of Circus of Books also serve as a metaphor for the invisibility of queer sex in public. In one of Ruscha’s images of the property from 1995, the façade is hidden by a bus; in 2007, a car blocks it from view. His photos barely reveal the colorful façade, and they do not depict the cruising customers or the store's products. These are visual accidents, the unintended consequences of Ruscha’s process, in which a chance encounter with a bus can obscure. At the same time, they operate metaphorically in telling ways, as visual reminders of a now largely vanished queer sex culture that today mostly takes place intangibly and outside the public sphere on dating apps, social media, and online porn websites. The obscuring bus and the car are neither a shame nor a shortcoming, but part of Circus of Books’s role in this queer utopia. We don’t really see anything because the point of cruising is to be invisible to everyone not cruising, especially a straight man’s camera. And it worked: there’s nothing to see here—and not just because of some unwanted vehicles.

Blending In: A Beauty Salon, a Jewelry Store, and Fine Dining Sex in Between

By keeping his camera outside, focused on exteriors alone, Ruscha avoided exploitation of queer culture. He did so despite the inherently loaded meaning of a straight white male photographing queer sites from the remove of a gazing camera. His nonjudgmental, outside observation allows a comparative study of queer sites’ façades that sometimes, as in the case of Circus of Books, provide limited, but still crucial, context. Ruscha also documented the way in which some queer spaces attempted to blend in—because they had to—yet still managed to direct customers in certain directions. Simultaneously, his photographs are signifiers of all the glorious stories taking place behind the façade that can sometimes only be gathered through oral histories.

Ruscha documented the way in which some queer spaces attempted to blend in—because they had to—yet still managed to direct customers in certain directions.

What might exceed most people’s imagination is what went on inside the gay male nightclub and bar The Numbers, located at 8029 Sunset Boulevard between 1976 and 1995. The ONE Archives' library supervisor and operations manager Bud Thomas describes The Numbers as follows: “You entered from the rear parking lot and went down a flight of stairs straight out of the House of Chanel (all mirrored). On one side of the room were upholstered booths with tables, and they served quite good food. On the other side was a full-length bar and, as I remember, some tables on the floor in between. There were mirrors above the bar and booths by the ceiling placed at a strategic angle where you could sit in one place and actually view almost anywhere in the room. The clientele was a mix of high-end rent boys (very good-looking and often porn actors) and older gentlemen looking for company. It had a very old-school white tablecloth supper club vibe [as] if it were directed by William Higgins.”22

Ruscha depicts the inconspicuous club amidst other inconspicuous businesses: in 1985, a jeweler to the east and a beauty salon and swimwear store to the west. By 1995, the jewelry shop had been replaced by an accountant, but a beauty salon (albeit under different ownership) was still there. This was an ideal site for a queer nightclub during the HIV/AIDS epidemic: the neighboring businesses closed at night and there were no customers left that might have bumped into guests going to or leaving The Numbers. Because The Numbers was not located in West Hollywood, or some other area with many queer bars and businesses, an obtrusive façade in this part of Sunset might have attracted more unwanted attention than an unspectacular one next to similarly unspectacular neighbors. While the club’s windowless façade did not stick out, its sign indicating parking in the rear showed customers the right way. Here, Ruscha’s photographs provide important aesthetic context while leaving the inside to the imagination.

The club name’s reference to John Rechy’s eponymous 1967 novel seems uncoincidental, given the people to whom it catered. The cruising novel tells the story of Johnny Rio, a gay man who returns to LA to prove that he’s still desirable, although he is not a young, muscular man anymore. His obsessive goal is to have sex with thirty men in ten days.23 Like the Black Cat, the name told it all through campy references for those who were privy to such knowledge and wanted to look behind the façade.

Conclusion: Cruising the Archive to Make Sense of a Straight Man's World

While the common narrative about queer sites of the past charts their rise from invisibility to visibility, Ruscha’s work suggests a more ambiguous story. The photographer’s lens depicts many queer sites becoming invisible over time, some remaining visible only in traces, and still others being adapted and appropriated by and for a broader clientele, often for commercial reasons. When paired with other formal and informal sources, Ruscha’s photographs help bring these visual traces and absences to life.

The photographs illuminate once-queer sites both directly—by adding historical visual context—and indirectly—by leaving much to the imagination due to the visual limitations of his approach. This visual record of queer history can then serve as an important basis for queer studies research and as an instrument for queer commemoration, precisely because of the photographs’ nonjudgmental quality and inherent disinterest in queer culture.

The photographs illuminate once-queer sites both directly—by adding historical visual context—and indirectly—by leaving much to the imagination due to the visual limitations of his approach.

Although Ruscha’s aesthetic of drive-by photography in motion overlaps with the queer perception of a city insofar as it depicts the same city with the same façades that everyone sees while driving down Sunset Boulevard, his is not a queer habitus. This is particularly so when it comes to what might be called queer scanning and zooming in or, simply, queer reading. This queer scanning occurs, for example, when trying to find queer bars or other places to flirt with people, buy homoerotic magazines, or have queer sex. Queer ways of navigating a city are based on underground guides and gossip, signs and symbols, a communitarian sensibility, and experiential knowledge. Such tools help make sense of a largely hostile (or simply irrelevant and boring) straight man's world, and, to some extent, even create a queer city. Thus, Ruscha’s photographs should not themselves be considered queer, even when they document queer sites.

Rather, Ruscha's aesthetic embodies a straight approach in that all of Sunset was available to him. He did not have to look for specific sites because it was all fair game. It is therefore not surprising that working with Ruscha’s image archive activates the queer sensitivity and life experience required to search for queer elements among a bevy of non-queer elements. Such is the quotidian practice embodied in the search for recognizable signs and symbols in, for example, the iconography of a “catwoman” or a pride flag, and especially in the practice of cruising and flirting with people that made it obligatory to read the signs.

At the same time that Ruscha’s photographs reflect a white straight man's worldview, his approach and the images themselves can be seen as protective documentation that avoided exposing queer communities and their places. That was not true of all documentarians in this period. A counterexample is Laud Humphreys, who conducted an ethnographic dissertation on bathroom cruising later published as Tearoom Trade in 1970.24 As sociologist Donald P. Warwick observed, Humphreys used “Systematic Observation Sheets” in which “space was provided for the time and place; the weather; the age, dress, general appearance, and automobile of the participants; their specific role in the activities; and a floor plan of the restroom. To be sure that the information was fresh, Humphreys took field notes in situ with the aid of a portable tape recorder hidden under a carton in the front seat of his car. He then sought to learn more about these men by finding their names, addresses, and the year and make of their cars in state license registers.”25 Humphreys’ unethical research on queer culture is just one early example of the larger structural problem of exposure and appropriation of queerness not only in scholarship, but also in art, film, and on television.

From a heteronormative perspective there is perhaps nothing repellent about Ruscha's work; but, from a queer perspective, the photographs inevitably attract and repel simultaneously.

While Ruscha should not be rewarded as a queer ally for his accidentally sensitive visual strategies for documenting queer sites alongside all of Sunset’s other sites, it is important to recognize that working with his image archive does not (re-)activate trauma. By contrast, because of its heteronormative qualities, it almost coerces a queer person to go cruising a straight man's city, with plenty of queerness to find and feel in and through his images. Put differently, from a heteronormative perspective there is perhaps nothing repellent about Ruscha's work; but, from a queer perspective, the photographs inevitably attract and repel simultaneously. His photographs are easy to work with because of their alluring, familiar aesthetic related to how we move through LA. They force a queer person to go cruising—as tedious as it might be—and do the queer work because most sites depicted are not queer.

To see and feel those queer sites and their histories, one need only animate the photographs through the memory and imagination that are important to any visual history of queerness, but fundamentally so to an accidentally queer visual history.

Notes

Acknowledgments: I thank the editors for their thorough and productive criticism and support; Eva Ehninger for the introduction to Ruscha’s work and the Getty's project and her support; and Luigi Valenti for his continuous, endless inspiration, flashes of genius, and loving compassion and support during this project and beyond. Without Bud Thomas's knowledge and help, nobody would ever have known about a Chanel staircase on Sunset. Furthermore, I’m grateful for the GRI’s help, namely Nathaniel Deines, Emily Pugh, Zanna Gilbert, and Megan Sallabedra. Research for this project was supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art (Immersion Semester in 2019/2020).